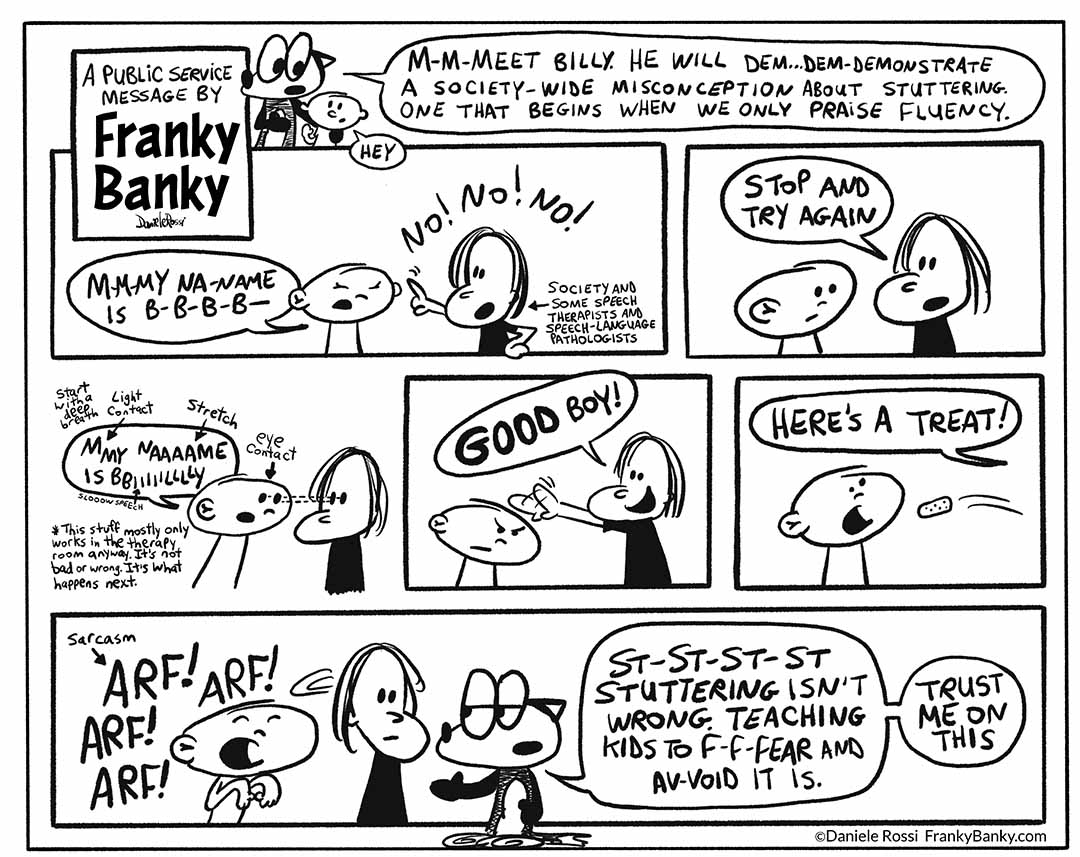

This comic strip contains seven panels. First panel. A cartoon fox named Franky Banky stands next to a little boy waving hello. Franky Banky stutters, me me meet Billy. He will dem dem demonstrate a society-wide misconception about stuttering. One that begins when we only praise fluency. Second panel. Billy is saying my my my nay name is buh buh buh. A woman representing society and some speech therapists and speech-language pathologists, shakes her finger at him ands shouts no no no! In the next panel, he tells Billy to stop and try again. In the next panel, Billy is using various, energy-exhausting speech-controlling techniques including starting with a deep breath, using light contact, stretching his words and maintaining strict eye contact to very slowly say “mmmmmmy naaaaaaame is Biiiiiiilly”. The lady pats his head in the next panel and says good boy. Then she offers him a treat in the proceeding panel. Billy sarcastically barks like a dog in the next and final panel while Franky Banky tells the lady stuff stuff stuttering isn’t wrong. Teaching kids to fee fee fear and avoid it is. Trust me on this.

Author’s commentary

In case you’re wondering, no, I’m not saying speech tools, fluency techniques, or fluency in general are wrong.

I drew this comic as a response after having recently learned about yet another disturbing method of speech therapy for stuttering where the child client is actually punished for stuttering and rewarded when speaking fluently.

In other words, don’t stutter or else.

And my question is… why?

Even if the child (or stutterer of any age) truly wants to learn speech tools, this approach is only instilling a fear of stuttering into the child and stifling his or her potential.

For example, a 10-year-old boy was inspired when he read the scene in my graphic novel, Tales of Mischief, Mayhem, and Mirth, where Franky Banky is interviewed on a radio station, stutter and all. The boy then gave a presentation about stuttering in front of his class on his own initiative later the same week. Stutter and all. He got an applause, and felt great afterwards. He then gave the same presentation to his entire school a month later.

Would it have been better to have punished this boy instead for not having spoken fluently? Would he be better off fearing stuttering the rest of his life? Should he also be told the lie that no girl would want to date him when he reaches his teenage years because he is confident enough to look stigma and adversity in the eye and live his life?

Or the 12-year old boy who, on his own initiative, walked up to the podium where I was MCing at a recent stutter camp, nonchalantly grabbed the microphone out of my hand and started telling jokes? Stutter and all. Would it have been better if I had told him he could proceed only if he hid his stutter?

Um, no.

Instead, I declared him my assistant and let him continue doing my MCing duties.

There would be no Franky Banky today if I was still fearing being caught stuttering because of the now outdated messaging I got from society growing up in the 1970s and 1980s. I learned otherwise thanks to having discovered a more realistic perspective and positive community of fellow stutterers.

Stuttering is ok

Really. Stuttering is ok. It’s how we talk.

The stigma of stuttering is not ok. That’s what has been causing all our problems.

Teaching a kid to fear stuttering is not ok.

Teaching a kid how to control their speech whenever they want to is ok. Just don’t make it into an award ceremony. Otherwise, you will potentially create harm. The harm in feeling inadequate because you can’t speak fluently outside of the therapy room along with a resentment towards speech therapists for having created the harm.

You can still be an effective communicator even when you stutter.

And quite frankly, fluency can never be achieved unless you “eventually grow out of it” which doesn’t happen for many. So why not put the focus more on addressing emotions, fear of stigma, and desensitization? After all, as Lee Reeves, CFO of Stuttering Therapy Resources, Inc, wrote back in 2010, “The decision to change the way we speak requires personal risk and will be met with both success and failure. With the foundation of acceptance, success is more sustainable and failure is less destructive.”

Yes, I still stutter.

Sometimes I use a speech tool when I feel like it. Lots of times I don’t.

Sometimes it feels good to stutter, sometimes it doesn’t. And thanks to having addressed stigma and desensitisation, I am able to easily brush off any negative emotions or feedback whenever they arise.

Fortunately, some speech therapists and therapy programs do reward overt stuttering. In other words, rewarding courage, bravery, and resilience. And the outcomes for success are far greater than any speech therapy based on counting disfluencies.

Unfortuantely, work still needs to be done. I had a conversation with a speech-language pathologist I met one evening at the ASHA convention a few years ago. The second I didn’t stutter on a sentence, she jumped in and enthusiastically informed me of that fact, it’s all in my mind, and it’s up to me to stutter or not. “The locus of control” she said.

I had to actually explain to an ASHA-licensed SLP that stuttering isn’t constant. The conference also had an exhibitor selling their video game where your player gets eaten by alligators every time he or she stutters.

Being different is normal. Perfection does not exist.

My aim here isn’t debating acceptance vs. fluency. That debate has been going on for decades and I don’t think it will ever go away any time soon. My aim here is the idea of rewarding passing off as perfect when perfection doesn’t actually exist.

We all want to be accepted. We are social beings. However, “being different, including having a disability, is actually normal,” to paraphrase speaker Chris Ruden. Chris doesn’t stutter, however, he is an amputee, type 1 diabetic record-holding powerlifter (who also beat two-handed lifters despite being told he’d never win any competitions because of his disability).

During an interview on the Always Looking Up podcast hosted by Jillian Curwin, Chris used the example of walking into a room full of people. Each individual regardless of having a disability or not, is different in one way or another. Height, eye colour, strengths, if someone is great in math, whatever. Being different is normal. It would be boring if everyone was the same. “We were designed to stand out. Not to be the same as everyone else.”

The two boys I mentioned earlier are going to grow up and kick some serious butt without having to fear stuttering. In fact, they already are.

August 4, 2025